Resolution

Schmesolution

(Best Movies of 1999)

The end of December has arrived, time for people everywhere to sit back and ponder the question, "What the heck is wrong with me?"

That's what the whole Resolution business is about, isn't it? Assessing one's flaws, choosing one that seems especially egregious, and vowing to correct it in the coming year. And every year, USAToday runs what looks to these eyes like the same statistics gauging the American Resolution failure rates, always abysmally high.

Which makes sense, because these so-called "flaws" are part of the

overall package, as much a part as the so-called "virtues." To suddenly

eliminate them from the program is the psychic equivalent of removing wolves

from the Yellowstone ecosystem--in the absence of that checking mechanism,

some other aspect, like deer, comes roaring into prominence, then excess.

For example, the other day I called the Anti-Molly Demi-Goddess Melanie, who

could out cuss a Tarintino movie whilst teaching a Relief Society lesson,

and noticed her end of the conversation was uncharacteristically bland (like

deer). I sensed a Resolution in progress, and she confirmed she was striving

cut down on unclean thoughts and language. A quick algebraic formula revealed

the dullness of discussion was directly proportional to the purity of Melanie's

thoughts and language. (Not that pure thoughts and language are inherently

boring, they just aren't, as yet, Melanie's idiom.) I told her I'd call back

in a month or so when that nonsense was over with.

"You mean after

I've shot that Resolution to hell?"

Pause. Then, "Goddam it."

Our chat became much more lively after that.

Another theory regarding the demise of most Resolutions is that deep down, people are content being who they are, that they inherently realize that change is dangerous and bad, and that's what makes them Resolution resistant rather than weakness of character.

Which brings me to Sharon's Picks for Best Movies of 1999!

The peerless The Thin Red Line continues to hold the number one position, and is expected to remain there well into the twenty first century. But beyond, way beyond, it lay five superior offerings with a common motif, that of characters defying their characters and the awful consequences that follow. They are, in order of when I saw them, Election; Eyes Wide Shut; South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut; Being John Malkovich; and Boys Don't Cry.

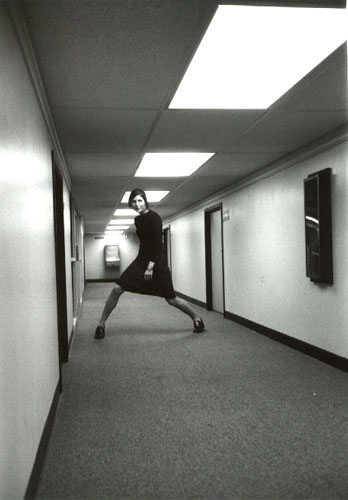

You Don't Know What She's Thinking (Eyes Wide Shut)

In both Election and Boys Don't Cry, the lead characters justify deceiving their communities as a moral imperative. In Election, Jim McAllister, the dedicated, multiple Golden Apple Award winning civics teacher simply must stop that over achieving bulldozer Tracy Flick from winning the Class Presidency, for the good of the school (which deserves diversity and equitable representation), the community (which--especially in the person of his best friend and neighbor--has been left damaged in the wake of Tracy's single mindedness), and Tracy herself (who would be humanized and humbled by a defeat, and aren't those qualities essential to sound leadership and a balanced life?). In Boys, misfit lesbian Teena Brandon becomes Brandon Teena--supportive, tender boyfriend (maybe husband?), and a welcome addition to a tiny Midwestern community. Neither could imagine opposition to a small, minute thing like electoral misconduct or bit of gender bending, not when their motives were so beneficent.

Election

McAllister and Brandon

are blinded by their good intentions, but a man honored for elucidating human

interaction and a woman always running from the wrath of the straight community

should have foreseen the backlash. They knew their crimes were minor in comparison

to the offences committed by those around them, but didn't understand that

that wasn't the point. Superambitious control freaks are supposed to lie and

cheat, not affable school teachers; and who would blame violent psychopaths

for being violent psychopaths? It's their nature and they never pretended

it wasn't, not like that girl.

Jim and Teena dared disturb the universe, they violated its predictable surface, and the price of its correction was McAllister's marriage and career, Brandon's life.

Head

Trips

The characters in Being

John Malkovich and Eyes Wide Shut wreck themselves while barely

impacting their communities.

Acting and puppeteering are the florid tropes for submission and control in BJM. Bodies are commandeered by strangers, but when an actor's (or child's) body is possessed the world does not notice, when a nobody vanishes into that body the world does not care. Individual individuals are not important to the social order.

Near the beginning of

Being John Malkovich, the puppeteer Craig Schwartz enters a porthole

to John Malkovich's brain, and leaves behind a piece of wood, a splinter in

the actor's mind. Near the end, Schwartz and the wood are expelled from Malkovich's

head after his months long occupation by a group of people who want to take

possession--the stick is gone, but the mind itself is irrevocably splintered.

John Malkovich, who when he entered his own porthole saw himself projected

in every person in the community, is himself invaded by a community, his body

overtaken by a body. In this movie, society functions because everyone in

it is consumed by monstrous egoism.

Monstrous egoism is also a problem in Eyes Wide Shut, one that is corrected

with stunning finality. Bill Harford is a handsome young doctor, so confident

in his splendid practice and of his beautiful wife that he chides his rich

employers for their excesses and flirts openly with models. Mrs. Harford is

so self-absorbed that she can't drag her eyes away from the mirror when her

husband makes love to her; but part of her narcissism is vested in insecurity--the

reflection proves her existence. You see, Mrs. Harford has lost her job in

an art gallery, and thus displaced she has begun to slip. Outside her realm

of competence, she spends her time puttering around the house, looking after

the kid, and taking lots of drugs. One night in a marijuana induced haze she

tells her husband about a sexual fantasy that has haunted her for two years.

Bill is so alarmed by the thought that he is not always and forever the center

of his wife's universe that he embarks on a quest to reassure himself of his

own importance.

It goes well, at first. The daughter of a patient comes onto him by her father's deathbed, a prostitute marvels at his generosity when he insists on paying her for services not rendered, he intervenes in the corruption of a child, and a woman sacrifices herself on his behalf when his cover is blown at an opulent orgy. An evening of high drama, all about Bill.

Except it isn't. When Dr. Bill cancels his appointments and tries to resume his adventures, he is made to realize how tangential his involvement in the big picture was: the patient's daughter is secure in her engagement, the prostitute is diagnosed with HIV, the child is thoroughly corrupted, and the orgies are for members only--and not the likes of Bill.

His most hallowed and harrowing notion, that a woman died to redeem him, is as lurid and untrue as his increasingly vivid imaginings of his wife with her would be lover. His client Victor Ziegler, an authentic Master of the Universe, finally clues him in. Far from being the hero of the drama, Bill was a bit player and a stooge. The role he played was genuine only to the extent that he nearly let it ruin his life.

Being John Malkovich (Low overhead--get it?)

The moral of these movies is this: no matter what desperate measure you take

to change you will be stuck forever with your essential self; best get used

to it.

So,

What's to be Done?

The antidote to America's "self-improvement" mania can be found

in the high minded low brow cartoon South Park: Bigger, Longer, and

Uncut. Reform runs rampant in Colorado after four third graders sneak

into an indecent Canadian movie (is there any other kind?). Their parents

mistakenly assumed it caused their darlings' moral degeneracy when in

fact all it did was teach them a few new words. Instead of honestly confronting

the Natural Child, the parents try to restore the kids to a fantastical

state of innocence. Their crusade comes to include censorship, aversion

therapy, self-immolation, war with Canada, and it nearly ushers in the

Apocalypse.

Meanwhile, Kenny is dispatched early in the film, denied heaven and thrust

into hell. He is a trailer trash boy with a vocabulary allegedly so foul that

his speech is completely obscured on the television South Park, and

in most of this deliriously obscene movie as well. He is killed in every episode,

perfunctorily mourned, devoured by rats, then forgotten. For most of the running

time of this movie, he watches Satan cavort with Saddam Hussein. In short,

Kenny embodies every fear the parents of South Park harbor for their children.

At the end of the movie, with the world on the brink of cataclysm, Kenny's death is revealed to be a mistake and he is given the power to change history. To everybody's astonishment, he opts only to alter those events that happened after his death--an act that will save the world, but keep him in hell for eternity. As a reward for his unselfishness, Kenny is elevated to heaven to frolic forever with topless angels.

Boys Don't Cry

In the Year 2000

These movies, coming

as the do on the cusp of a new millennium, are telling us something, and

I think we should listen. With the hysteria surrounding the end of the

century/millennium, from the doomsayers of the Y2K catastrophe to those

disappointed that we're not flying hovercraft to work, the best fin

de cycle movies have responded with a essentialist backlash. Election,

Boys Don't Cry, Being John Malkovich, Eyes Wide Shut, South Park: BL&U,

plus top movie contenders Fight Club, The Talented Mr. Ripley,

and The Iron Giant are fables about the dangers of betraying one's

own true self.

The drama is in discovering (or not) who that self is and recognizing the disparity between who what is and what was imagined. The befuddled creatures in BJM never find their fundamental beings even though they are utter egoists, preferring instead to engage in ever more grotesque masquerades ("Don't stand in the way of my actualization as a man!")

Satan & Saddam in South Park: Bigger, Longer,

Uncut

Eyes Wide Shut

Tom in The Talented Mr. Ripley and The Narrator in Fight Club

trade away as much of themselves as they can--even their names--but can't

escape the essence that remains, now poisoned and horrified at the costs of

the alterations. Dr. Harford in EWS on the other hand learned his place

so well that the smirk was wiped off of Tom Cruise's face for the first time

in his nearly twenty year career.

The community will enforce identity integrity to the best of its ability, as in Election and Boys, but the only genuine measure is an honest internal audit. The Iron Giant tests himself and is satisfied that he "is not a gun," and Kenny saves humanity and his soul without changing anything about himself.

If you must make a resolution this year, nix "improvement" and consider becoming more like yourselves.