See Signs and Wonder...

Why on Earth do People Take M. Night Shyamalan Seriously?

Signs director M. Night Shyamalan has managed to attain unprecedented critical and popular acceptance considering his three features all fall within the supernatural/ horror category. Though he uses/ abuses genre conventions, his work clearly aims to be profound, instructional. He handles his paranormal tropes so trivially, and paces his films so slowly, that viewers can hardly help but take note of the stories’ messages—if only as a defense against drowsily drooping head first into a bucket of butter flavored popcorn. Otherwise, the audience has nothing to do but spend whole minutes wondering if Bruce Willis or Mel Gibson will… ever… make… it… across… the… room.

Now, movies in these genres foreground their theses as a matter of course. For example, you don’t spend a lot of time looking at the unusual though decidedly phallic protrusions in movies like Rabid or From Beyond wondering what the filmmakers had in mind. But where true horror movies grapple with difficult, insoluble problems (evil exists, death happens, sex is sometimes alarming), Shyamalan offers simple, comforting solutions (psychotherapy works, superheroes exist, faith is worthwhile) in defiance of some genuinely horrible stuff he builds into his stories. His movies’ twist endings have led some to compare them to Twilight Zone episodes, but that does a grave injustice to the series. The Twilight Zone was a fiercely moral realm, where shockingly rough justice was dispensed to villain and schnook alike for even small ethical indiscretions. Shyamalan movies are more like pop-up Hallmark cards that say, "BOO!" And while I can, in theory, appreciate the appeal of bland, timid, star-driven "horror" movies, and understand, in theory, why they make money hand over fist, Signs goes too far. It’s just so bloody stupid.

The central problem in Signs is not "will alien invaders conquer earth and devour its inhabitants," but "will former minister Graham Hess (Mel Gibson) reclaim his Christian faith?"

Matters of faith and redemption deserve serious consideration and are certainly worthy of big screen treatment. Considering the above scenario, however, you have to question the movie’s priorities. Especially in light of how terribly fragile Hess’s faith turns out to be.

The death of his wife, which led him to defrock himself and abandon his flock, is shown in stages throughout the movie, which gives it a built-in portentousness. But as unexpected deaths go, Mrs. Hess’s is one of the mildest imaginable. Pinned to a tree by a truck, her lower half is essentially severed. Though gruesome, her death is painless, and so long in coming that the sheriff has time to arrive, call the ambulance, and call Graham. He has time to arrive, listen to an excruciatingly slow description of his wife’s injuries, and rush (kind of) to her side. She has time to murmur words of affection, advice, and (as it turns out) prophesy, all while looking pretty great for somebody who’s been cut in half. The man who cut her in half (M. Night Shyamalan himself in a small role) was neighbor and friend, and genuinely sorry about falling asleep at the wheel.

Granted, the death of a loved one is sad and traumatic. But honestly, is the above the sort of thing that should cause a minister to lose his faith in God? In combination with Hess’s admonition to his family to steer clear of a teenage girl so innocent she believes she might go to hell for calling her boyfriend a rude name, and his prissy refusal to shout bad words at a mysterious intruder, the viewer must conclude that Hess’s sensibilities are so surpassingly dainty as to be unworthy of serious consideration.

The townspeople adore him, however, and persist in calling him "Father" even though he cringes every time they do. While it’s nice that they still hold him in high regard, months after his abdication you’d think they would have found a replacement.

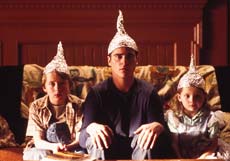

A gripping scene in which the actors watch TV.

The town itself doesn’t seem particularly cut off from the mainstream. They have all the modern conveniences: cable television (even in remote farmhouses), a pharmacy, a military recruiting office on the pretty main street area, etc. The town veterinarian (Shyamalan) is of conspicuously Middle Eastern or Indian origin, though his relatively exotic appearance is never remarked upon and any practical difference apparently too mundane to mention. All of the characters dress and speak in absolutely middle class American style, with the bizarre exception of the bookstore owners who are unkempt, slack-jawed, hayseeds. When Graham’s little boy Morgan asks if they have any books on the paranormal, the proprietress says, "Wall, I thank we got wun wunse for the city pee-puhl."

Books on UFOs and abduction phenomenon have been in the mainstream for over a decade, and the store seemed clean, open and well stocked; less a grimy rural bookmobile than a Barnes & Noble in miniature. They might at least have a dusty copy of Communion lying around. Especially since the owner’s husband seems to have a taste for weird conspiracy theories (he thinks the crop circles are a plot to sell sody-pop, and as evidence the points to the antique Shasta commercial that repeatedly runs during circle coverage). In this movie, the bookstore is the intellectual nadir of the community, which becomes more cosmopolitan the further away from the city center one travels.

Fortunately, the one book on UFOs the bookstore has is a doozy. Against all odds, it describes the alien invasion in minute detail. There’s even a picture in it of a UFO attacking a house that bears an uncanny resemblance to the Hess place. It’s a variation on the B- movie convention of the small town’s elderly scientist (or virile high school science teacher) who always seems to have a slideshow at hand explaining the strange phenomena, yet far less plausible.

But that’s in keeping with the aliens themselves. Ah, the aliens! Where to begin? The best thing Shyamalan does is keep them out of sight most of the time. In a monster movie, which for all its pretensions Signs is, a less is more strategy is often wise—but in this case, less is just really, really less. When they are finally revealed, the aliens are dead ringers for Swamp Thing. Perhaps it’s perversely admirable for Shyamalan to have taken such a low tech approach, but things have come to a pretty pass when Disney movie sinks to stealing props from Troma Films. The internationally broadcast video of an alien mincing around the perimeter of a child’s birthday party in Brazil is so cheesy and amateurish it would give the producers of Sightings pause, and yet is taken as evidence of a grave threat by the world’s media in Signs. If the videotape had gone on to show something frightening, like children being harmed or threatened in some way, maybe some panic would be in order. If the newscast had even reported that children had been harmed or threatened, maybe some panic would be in order. But it’s hard to get into a sweat over a scrawny humanoid in a moss green body suit that doesn’t take out even one eight-year-old.

This is not to say all movie aliens must be scary, or scary in the same way. But if you have a movie alien and it’s supposed to be scary, how about giving it a little muscle? Or barring that, logic?

The perpetrator at the scene of the crime, M. Night Shyamalan.

This is a species that travels to earth in legion to eat humans, but they hunt as individuals. They are strong enough to leap onto a second story farmhouse roof, but captured by a mild mannered veterinarian who suffers nary a scratch in the process. They can batter down wooden doors, and effortlessly discover coal shoots even the homeowners had forgotten about, but don’t think to escape from a pantry by breaking a window. They approach earth completely undetected, but upon arrival their communications are picked up by baby monitors.

Perhaps the greatest outrage to common sense (in this movie, there are a lot of contenders) is in the way in which the aliens are ultimately defeated. After several days of terror, a news report indicates some primitive Middle Eastern tribesmen have devised a way to kill the aliens. When Graham Hess and his brother Merrill happen upon the solution, we learn it is—brace yourselves—pouring water on them and hitting them with a bat.

As it turns out, water burns them like acid, and they react to a good pummeling just like any other fleshy creature. By the time the invasion reaches a crisis at the Hess home, Graham had already cut the fingers off the alien trapped in the vet’s pantry with an ordinary kitchen knife (oddly, even though little was known about the aliens at that time, Graham did not think to call the police, or the news, or the ASPCA about the captive). That should have put any fears of the creatures’ invincibility into question, but when his house comes under attack, he doesn’t think to round up cutlery of any sort. Besides, I can’t help but think hitting aliens with sticks would be well within the American can-do, don’t-tread-on-me, make-my-day-punk ethos and not exclusive to Middle Easterners.

But okay, fine. Graham and Merrill cower like little girls until Graham remembers his wife’s deathbed message that Merrill should swing his bat really hard. It’s not a movie about heroics (by any stretch of the imagination), and who knows what I would have done in similar circumstances, etc. The thing about the water, though, is insane. These aliens hunt and eat humans, which are composed of about 98% water, on a planet where water covers over two thirds of the surface. Even if they could manage the environment, how can they survive their diet? And supposing they figured that out, why would they risk visiting a wet place like Pennsylvania where a rain shower or heavy dew could be lethal? Especially when they could go to a nice dry place like Zimbabwe or North Korea, eat to their hearts’ content, and save the respective dictators the bother of starving their people to death. Why leave signs in nice juicy crops when there are millions of acres of desert to play with?

Well, it all goes back to Hess’s faith, and recovery of same. The reason primitive Middle Eastern tribesmen figure out the big whoop secret to surviving the alien attack (the water part seems especially dubious coming from such an arid region) is because that is the origin of three great world religions—including the one to which Graham until recently subscribed. The reason they shrink from water like vampires from holy water is because they abhor a baptism. And the reason Graham regains his faith is because his son just happens to have had a severe asthma attack which closed his lungs to the poison gas the alien sprayed in his face, and that somehow cancels out his wife’s bad luck. This is the only movie I can think of that would have been less pathetic if the protagonist had awoken and realized it was all a dream.

I hate this freakin' movie so freakin' much...

Signs isn’t just preposterous, it’s an insult. Nothing but nothing in it rings true emotionally or intellectually, and human sensibility takes a beating. Because M. Night Shyamalan’s movies are relatively gore free, he is given credit for a humanitarianism denied to virtually every other director who works in the horror/ supernatural genre. And while it’s true there are some indefensible bloodbaths sitting on the shelves of any Blockbuster franchise, Shyamalan’s prim hiding of the bodies exanguinates the horror and the morality from horror movies. The reason The Sixth Sense worked to the extent it did was because the ghosts were shown as plainly as the boy saw them, often broken and bloody. The frankness of the ghosts’ appearance give the viewer a glimpse of the boy’s grim reality. But in the unbearable Unbreakable, a character commits hundreds of murders, but the extent of the carnage is glimpsed only in news reports throughout the movie. To show even a fraction of the dead may have been brutal to some tender eyes, but to casually allude to such tragic statistics without putting them into some context of grief and suffering beyond Bruce Willis’s somnambulant survivor is far more obscene.

In Signs, an alien invasion occurs and people are killed—but that has no impact whatsoever on Graham Hess’s beliefs since he didn’t know any of them. The aliens, as silly as they were, didn’t move him to question the order of the universe (what role in God’s plan do flesh eating aliens play? in whose image were they created? etc.) the way a couple twists of fate that claimed his wife and spared his son did. Shyamalan exploits and burlesques faith, but doesn’t seem to have a clue what it is.

In short, Signs is a tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing.