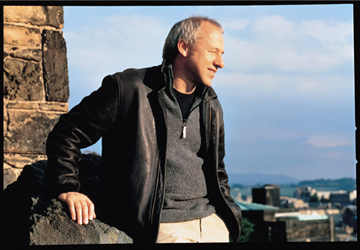

A few months ago, I bought Mark Knopfler's most recent cd Sailing to Philadelphia and showed it to Patrick. After opening the jewel case and looking at the picture of Knopfler with his receding gray hairline cut short, his black sports coat with an immaculate white shirt open at the collar, sitting on a crate, hunched over a guitar, Patrick said, "That guy has no rock left in him at all." And that was before he learned that Knopfler sang a song with James Taylor on the album.

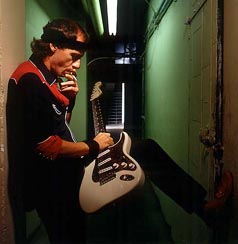

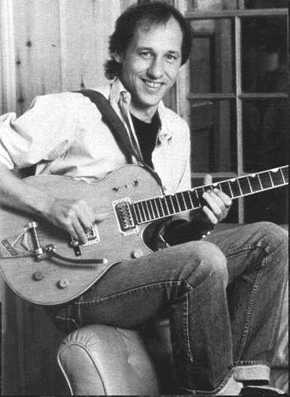

I was irritated and dismissive on Knopfler's behalf. In an age when rock has elder statesmen, and a lot of them are not nearly as embarrassing as had been predicted, I wanted to assert Mark Knopfler's prominence in their guild. He belongs there. As the singer/songwriter/lead guitarist for the band Dire Straits (the DS song and video "Money for Nothing" hit the airwaves just as MTV was gaining prominence and helped make the album Brothers in Arms an eighties phenomenon) and sideman for the likes of Van Morrison, Bob Dylan, and Tina Turner, his music will be heard on classic rock stations forever.

On the other hand, and it kills me to admit this, Patrick has a point. Although Mark Knopfler has impeccable rock ability and credentials, that isn't what made his music unique and isn't what is going to make it last. What will is the sense of space he conveys behind the notes he plays, the way his songs become environments-music that sounds like a cloudy sky, blue and backlit by stars.

For instance, on Dire Straits's third and best album, Making Movies (produced by Jimmy Iovine). The first song, "Tunnel of Love," begins with Roger and Hammerstein's "Carousel Waltz" on a wheezey old harmonium with guest pianist Roy Bittan (from the E-Street Band) playing counterpoint below. The sound is soft and distant, as if its source its source-the carnival-is hidden in a glen. Then the organ holds its final note while the piano abandons melody to repeat an escalating three note refrain, gradually louder and faster, then with a grace note at the beginning so when the first guitar chord and drum beat are simultaneously struck the time signature has been changed from 3/ 4 to 2/ 2. The change in music matches the change in scene-it's as if you've crested the hill and the carnival is laid out below with all its light and sound and excitement-then Knopfler's descending guitar notes pull you headlong into it.

You could get rude at this point and say that it's because Knopfler doesn't sing on the album. While it's true that his voice is low key to the point of no key, I'm not persuaded that that's a bad thing. Rock has a unique tolerance for uncommon voices, and Knopfler's unemphatic grumble is the ideal vehicle for his prosy lyrics. A former schoolteacher and journalist, he has a knack for telling detail that doesn't depend on a lot of drama. For example, his evocation of empathy and distance in "Hand in Hand" from Making Movies:

As you'd

sleep, I thought my heart would break in two

I'd kiss your cheek, I'd stop myself from waking you

But in the dark you'd speak my name

You'd say, "Baby, what's wrong?"

Then on "Skateway" from the same album--which will be the theme song of the TV show based upon my life--his voice swells and breaks with vicarious joy. Aureng Zebe is absolutely correct in stating Rollergirl (whose character was appropriated and desecrated in the awful Boogie Nights) is pop music's equivalent to the heroine of Wallace Stevens's "The Idea of Order in Key West," creating "her own world in the city."

No rock left at all--But how bad is that?

Written by Sharon C. McGovern

From

Vol. 29

Back to Cobra Music

Other

Mark Knopfler/ Dire Straits Links: Brothers

in Arms: Dire Straits Site

Geocities

Dire Straits/ Mark Knopfler Site

Neck

and Neck: Mark Knopfler Site